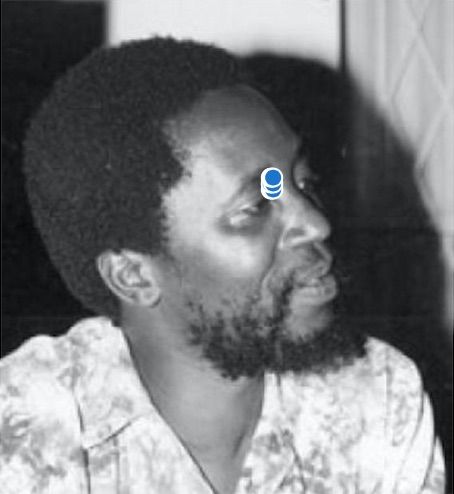

Chenjerai Hove

Chenjerai Hove was a prolific poet whose literary work was humorous, hard hitting and educative. From 1982 till his death in July 2015, Hove dedicated his time to writing short stories and poems that depicted the struggles and travails of Zimbabweans under the autocratic rule of President Robert Mugabe who has ruled the country since independence from Britain in 1980. Hove died in exile in Norway on 12 July 2015.

In his tribute to Chenjerai Hove, Morgan Mugove Changamire argues that Hove ‘was forced and chased into exile by the system at the height of political violence and repression in 2001’ adding, ‘they trailed him and made threatening calls in the middle of the night… Fearing for his life, Chenjerai Hove skipped the country leaving behind his beloved wife, children, close friends and relatives. Hove loved this great nation and its people.’

According to a Zimbabwean scholar, Jenjekwa Vincent, two of Chenjerai Hove’s best known works, Blind Moon and Palaver Finish ‘complement each other in presenting Hove’s disillusionment, frustration, protest and anger at the level of betrayal displayed by political leaders of independent Zimbabwe’. This explains why Hove ‘was tormented and haunted by men and women in dark glasses day and night.’

Chenjerai Hove’s frustration with President Mugabe’s broken promises can be understood from the vantage point of his high hopes at independence following a brutal guerrilla warfare. Having been born and raised during the colonial era, Hove had first-hand experience of the brutality of the colonial regime on black Zimbabweans. It is no wonder his earlier works were on the suffering endured by black Zimbabwe during the liberation struggle. In 1985 he produced Up In Arms, a collection of poems that bemoaned the ill-treatment and harassment of blacks by whites during the colonial era. This narrative continues in the Red Hills Of Home wherein he berates the colonial regime for desecrating black communities by destroying burial sites and other sacred sites such that the village is ‘home no more’. But Hove was not a racist. He addressed issues not colour.

However, when President Mugabe’s government began to deviate from the ideals of the liberation struggles Chenjerai Hove was available to protest through poet. In Rainbows in the Dust Hove bemoans the crisis of governance, often referring to the ruling party as the ‘ruining party’ and went further to argue that ‘armoured cars, guns, poison’ are instruments used by ‘a tyrant in State house’ to ‘silence the nation’. In the Blind Moon Hove condemned the personality cult that was now evident among the ruling elites who had now personalised and privatized the people’s struggle and now felt entitled to rule perpetually. This resulted in Hove being a marked man by the ruling elites resulting in him leaving the country in 2001.

Hove continue to write profoundly on developments in his country. In 2003 he wrote he best known work in exile, The Palaver Finish, in which he decried the violence unleashed in rural areas by the ruing ZANU PF party. In one of the essays in the book, ‘The new millennium in the village’, Hove explains how villagers who oppose the ruling party, especially at election time, are earmarked for torture by politicians in that area:

Defenceless, and isolated in his own homestead, the young boys and girls employed to kill will arrive at any time and kill the villager and his family. He is lucky if he is beaten and left for dead, maybe he will find someone to take him to the clinic on a donkey cart.

The death of Chenjerai Hove in exile in Norway united Zimbabweans at home and abroad in celebrating the life of a man who spoke most effectively and eloquently through his pen. “Chenjerai was a national treasure," said Wilf Mbanga, editor of the UK-based The Zimbabwean. "It is such a tragedy that one of Zimbabwe's best known writers was hounded out of his country and forced to live – and die – in exile. He was never afraid to speak the truth, no matter however painful that might be."

The importance of Chenjerai Hove’s life and works can be measured by the harsh criticism he received from a local newspaper aligned to President Mugabe’s ruling ZANU PF party. In their tribute to Hove The Patriot weekly described his decision to go into exile as an act of ‘opportunism’, adding that ‘he envisaged a massive hero’s return in a few years with cameras flashing at Harare International Airport while he read a triumphant statement about the monumental effort it required to get ZANU PF out of power’. Whilst this statement must be dismissed with the contempt it deserves, it underscores the befitting larger than life status that Hove was accorded by both friends and foes and that the he, being dead, still speaks to us.

It is therefore overwhelmingly befitting to posthumously confer upon Chenjerai Hove this Giraffe Heroes honour.