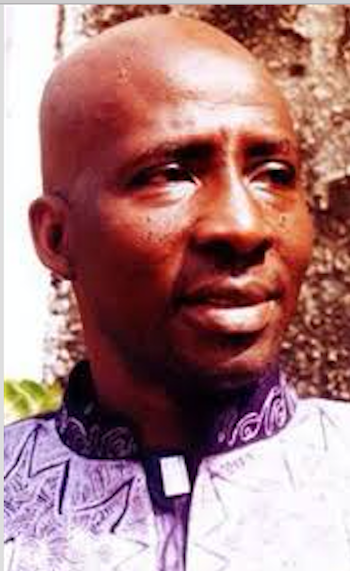

Jonathan Leigh

Summary: Jonathan Leigh is the managing editor of Sierra Leone’s Independent Observer newspaper. Not shy about expressing his views, he continually risks arrest and imprisonment by the government as a result of his editorials. In 2013-2014, he and a colleague spent a year in confinement because of a Sierra Leone law hampering journalistic freedoms—specifically, an editorial questioning the integrity of President Koroma. The two editors were released only after pleading guilty to a conspiracy charge. Leigh continues to challenge the government in his role as editor.

Profile: On March 10, 2014, Jonathan Leigh, the outspoken managing editor of Sierra Leone’s Independent Observer newspaper, pled guilty to a single count of conspiracy to defame President Ernest Bai Koroma. Leigh had faced 26 counts of criminal libel, sedition, and conspiracy for an editorial critical of the president. He and a fellow editor were arrested the day after the editorial appeared. The 25 remaining charges were dropped prior to the final hearing but Leigh was pressured into pleading guilty to the conspiracy charge, in return for which the judge let him off with a caution.

Thus ended a 10-hearing ordeal that has called into question Sierra Leone’s ability to grant freedom of expression. As Cléa Kahn-Sriber, the head of the Reporters Without Borders Africa desk, pointed out, “Jonathan being forced to plead guilty to a conspiracy charge is no mark of honor for the country’s institutions.” Leigh, who had been arrested on October 18, 2013, wasn’t released until over a year later; he and his editor each paid a bail of 85,000 euros.

Leigh was arrested under Sierra Leone’s Public Order Act of 1965, which states that anyone who prints, publishes, sells, offers for sale, distributes, or reproduces any “seditious” publication can be found guilty of a criminal offense and serve up to a three-year prison sentence. Many organizations—inside and outside Sierra Leone—have been pushing for a revocation of the act, claiming that it stifles legitimate dissent. Further, the act serves as a springboard for political harassment of journalists and others challenging the government. Kahn-Sriber says that “The government’s policy of harassing the media is a threat to fundamental freedoms. The authorities use criminal defamation and sedition charges to intimidate journalists and then allow the proceedings to drag on in order to keep up the pressure.”

One of the organizations that have supported Leigh is Amnesty International, which was very clear about its position: “High-level government officials must be prepared to face public criticism about how they carry out their office. To refuse a space for such criticism and public accountability is a violation of the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by Sierra Leonean and international law.”

Leigh persists in exercising what is left of his journalistic freedom. He still manages the Independent Observer. Since his release, he has angered the government several more times and has continually risked arrest and imprisonment. And he remains a strong voice calling on the Sierra Leone government to rescind the Public Order Act. If people are not allowed to voice their opinions, he maintains, then the rule of democracy will be rendered virtually meaningless.