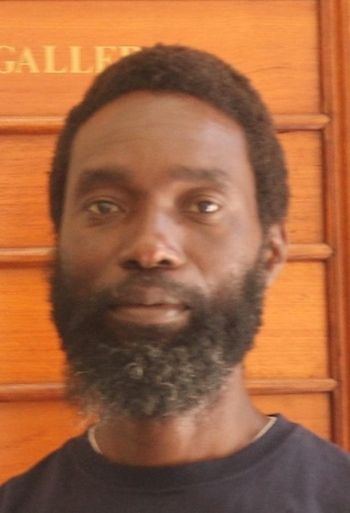

Merlin Mosoko

Summary: Merlin Ekwanza Mosoko, a professional basketball coach, uses sports to build social cohesion in the Cape Flats, a region in northern Cape Town rocked by violence, division and teen pregnancies. He raises enough money from his job to start basketball teams targeting young people to keep them away from drugs and gang violence, to teach life skills and to keep kids in school—all promoting a better future.

On paragraphy 6 of Mosoko's profile, when he moved to delt with his family- wife and child, he bought a basket ball as a strategy to attract other childrens to thé play. As his child would be playing in thé street, other children got attracted," I bought a basket ball for my son so that other children would be attracted. Thus how i had my first basket ball team in Delft," said Mosoko. This was a community where sport was not valued.

On thé last paragraphy, one of thé children between thé two who won thé basket ball championship is his child.

Profile: Merlin Ekwanza Mosoko, a professional basketball coach, uses sports to build social cohesion in the Cape Flats, a region in northern Cape Town rocked by violence, division and teen pregnancies. In Cape Flats, blacks and coloreds on one hand and foreigners and locals on the other hand don’t see eye to eye, yet they live in the same community. So Mosoko, originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, formed Umoja, an initiative that sought to promote unity and combat suspicion, mistrust and xenophobia in his community through sports.

In 2002, while living in Nyanga, dubbed the murder city of South Africa, Mosoko started a basketball team, to encourage boys to be nonviolent and keep them busy. ‘I realized that children spent most of their time throwing stones and fighting each other and I said children cannot grow up like this. Let me help my community to learn basketball so that all those kids who spend most of their time in the street do something constructive,’ said Mosoko.

With the help of a local organization, he bought two basketballs. On seeing his vision, a local school offered him grounds. He took the opportunity to involve learners from this school, and a few surrounding schools.

In 2005, he organized a tournament, involving two schools and children from a refugee camp. The objective was to bring together African youth—foreigners and locals alike—for a good cause. ‘It helped refugee children to feel that they have a right to go anywhere in South Africa, to enjoy themselves; they didn’t have to live in a camp, excluded, ‘said Mosoko. After the tournament, he formed a team consisting of boys of mixed backgrounds and registered it in the Cape Town Basketball Association, giving these boys greater exposure to the larger community.

In 2006, Mosoko moved to Delft, another local township known for gang violence, human and drug trafficking. He set up the Umoja Delft Basketball Club, targeting kids aged 7-9 years. However, in Delft, in the beginning, there was no interest in or infrastructure for basketball, but only for netball. He had to improvise. He started by setting up a hoop at home. When other boys saw his own son playing with a basketball, they wanted to join in. From that, Mosoko built his first team. At first, there was only a netball grounds with poles so I had to make lines to create a basketball court,’ Mosoko remembers. Eventually the City of Cape Town gave the Club a proper basketball court to practice on.

Umoja is a Swahili word which means unite, so as its name suggests, the Umoja Delft Basketball Club is meant not only to promote a sport, but to unite coloreds and blacks who often fought in gang wars, riddled with mistrust and suspicion. Life in the neighborhoods where Mosoko works is not predictable. Both he and the children he coaches are exposed to danger. Cases of people either killed by stray bullets or in robberies have been widely reported.

‘It can be a risk just calling the kids to practice, especially during the week,’ Mosoko says. ‘Some kids complain of meeting gang members along the way who, mainly under the influence of drugs, don’t hesitate to attack,’ said Mosoko.

‘There are many things that can happen, but we don’t think of that,’ he continues. ‘We just live our lives—that is what I tell my kids. Let us live our lives and enjoy ourselves. Anything can happen anytime. We are not in great danger from those who know us, but others who do not know us can rob and harm us.’

Mosoko also sometimes faces resistance from some parents who feel that gangsterism is a culture and a way of life. ‘In some communities,’ he says, ‘children are initiated at a very tender age and gang culture is glorified. I have met some parents who say ‘don’t disturb my kids because we want them to have another way of life and not your way.’

The Umoja Delft Basketball Club also consist of girls, in a move meant to combat child marriages and teen pregnancies that often lead to school dropout in this community. ‘My club is mixed—boys and girls. In my community, I don’t want to see girls impregnated. It’s not good for me especially as a parent. They must also be busy with sports,’ said Mosoko.

By sticking his neck out and risking his own safety to improve the lives of boys and girls, Mosoko gets respect from community members, including most parents, who sometimes support him with money and food when his kids go for training.

Umoja Delft Basketball Club was registered with the Cape Town Basketball Association and, in 2018, a team Mosoko had groomed won the Association championship and two outstanding players—one of them his own son—got scholarships to study at an elite school. Mosoko felt that his dream has been fulfilled—to nurture the values of love and principles of responsibility in this young generation, and to help kids grow up with some skills, to encourage them to learn and have a good education, and a better future.